One man’s journey from a Dairy Farm in Lincklaen to the World of Antique Cars

Kathy O'Hara

Published, May 22, 1997

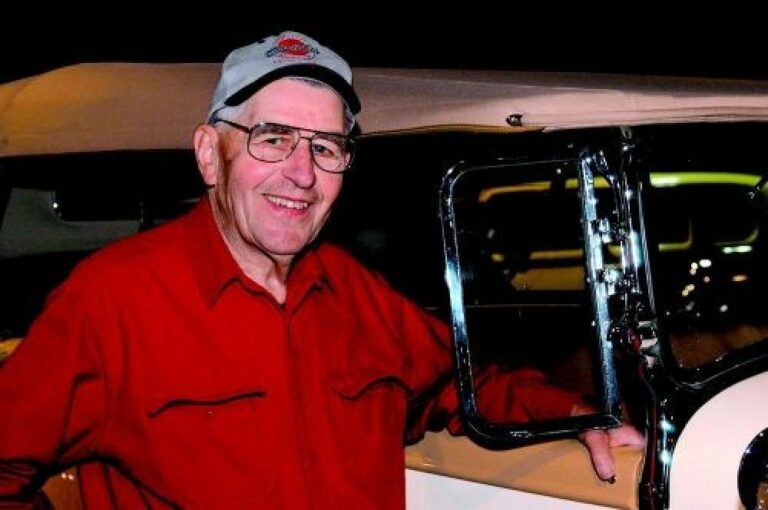

A special edition of The Evening Sun for the opening of the Northeast Classic Car Museum.

When he was five, his family moved to the present family homestead in Lincklaen, a farm on the Dublin Road. “It was a good running farm.” said Staley of the years after the war to end all wars. In time, his father introduced a pasteurizing and bottling operation for the farm and then selling produce in DeRuyter. The legend “Staley’s Dairy” appeared on the side of the milk truck. One of those trucks, now restored, is part of the opening exhibition of the Northeast Classic Car Museum.

The farm is still a working farm, but it is rented out to others to run. George Staley is a little busy. “The reason I kept the farm is not only because it is the home farm,” he said. “It is operating because you have to have some reason for paying taxes.” Staley is well aware of the financial crunch facing small farms today. He may love the road, but he loves the good earth as well.

The Life and Times of George Staley

Staley attended DeRuyter High School (as did his prospective wife) and then in 1937,enrolled in state of New York Aviation Training School in Utica. The state-sanctioned school offered training to become an air mechanic. The school closed and then reopened as engineering specializing in air and power plants. It was there that Staley received his federal license after 18 months education. Young Staley went to work for Martin Aircraft in Baltimore. Following that, he put in a stint at TWA.

Then came the war. By then Staley was a crackerjack carburetor engineer working for the Bendix Corporation. He had special classification that protected him from the draft because he was considered essential war personnel. As bureaucracies are prone to do, someone shuffled the wrong paper and Staley received his draft notice. “Don’t worry about it” he was told, “We’ll take care of it.” Later he was ordered to report for his physical. “No bother, it’s all taken care of,” said the Bendix honchos. The next thing Staley knew, he was shipped off to South America to check aircraft engines. From there, he went to Africa, stopping at all the naval bases and setting up carburetors in planes. During these months of travel, Staley said he had to wear an officer’s uniform. He had on the uniform of a naval officer and braid on the cap which identified him as such, but there were no stripes on the sleeves. “I would walk outside in my uniform and men would prepare to solute me and stop with their hands halfway up to their forehead,” they were puzzled as they walked away.

Staley moved to the Boeing Company where he was given an Air Corps uniform to wear. He was sent by the company to Windover, Utah. There, he was assigned to the 509th Bomber Group as a technician on a new fuel injection system. “They were going to drop ‘the bomb,’” said Staley. He said the B-29s had a fuel system that sometimes failed. “And they couldn’t have that with the atomic bomb,” he said. And so they refined it until it was perfect

Staley was moved to Tinian. “Col. Tibbits was my boss and I made sure the Enola Gay was ready for the mission,” said Staley. He said he and others knew something big was afoot but they were not sure what. The entire mission was shrouded in secrecy. He did know the Enola Gay had a bomb bay much bigger than the standard. Even with only Air Force men on the island, the plane was guarded both day and night by military police. “At night the bomb was dropped into the pit and we all knew this was the day,” said Staley. He had done a lot of work with photography and when he heard over the radio the bomb had been dropped, Staley went out and waited for the craft to return. By now, he and the others had been briefed on what had taken place. As the plane taxied down the runway, Staley moved his jeep into position. The crew of the bomber, with Tibbits at the head, posed for pictures. The commanding officer came out and pinned the Distinguished Service Cross on Tibbits’ chest. Staley was certain he had the only color photos of that momentous occasion.

“A couple of years ago, I took the pictures to the Smithsonian Institution when they were mounting their exhibit of the Enola Gay,” said Staley. Experts at the museum told him that indeed, yes, these were the only color photos of that moment in history. He donated the photos to the nation’s museum. Reflecting on the event years later, Staley is certain the proper decision was made regarding the bomb. “I thought it was the right thing.” He said, “If we had invaded them it would have cost so many more lives.” Staley said this is true even of the Japanese population. He said the first bomb killed perhaps 10,000 Japanese. Nagasaki added to the toll, but it would have been much more terrible if the war had continued. America had used its two bombs but there was another in reserve, he said, one that could have decimated the population.

When Staley returned from the war, he gravitated toward another job in his chosen field after working with TWA on the Lockheed Constellation. He joined a company that had a contract to overhaul 345 Franklin engines. “The engines were air cooled and that’s when I really got interested in the Franklins,” said Staley. It was only a coincidence the cars had been manufactured close to his home. “I bought my first car about 1962,” said Staley. And that purchase heralded the beginning of what would become a gold medal collection in the world of antique automobiles.

“Not to be impertinent, Mr. Staley, but somewhere along the way you had to of picked up a ton of money”. Staley laughed and gave his stock answer “I really didn’t start collecting seriously until I retired a started drawing social security.” He said when he has been showing cars and someone asks that question, he does feel the questioner is impertinent, especially calling out the question in front of a group of people. “The collection is worth what someone offers to pay for it,” said Staley. Recently, he explained, a Duesenberg was sold at the high end of the spectrum. They sell for anything from $350,000 to $1.3 million. But measurement is always the number the buyer is willing to pay. The worth of his own collection, said Staley is unanswerable.

And, the source of the money? That, said Staley came from a company he started with three other men in 1950. The company was in the business of overhauling aircraft accessories. The company grew from two or three employees to 250 people in 1989 and had a presence at MacArthur Field on Long Island, Fort Lauderdale and Dallas. “Then I sold out to UNC and took the money and ran,” said Staley with a chuckle. “I came back home,” said Staley, “And started building garages.” Although 51 of the Staley automobiles are now housed temporarily in Norwich, there is still plenty of fascination and lore in the vehicles sitting in the buildings. There are Packards and Franklins and the rest and two wonderful “oddities.” The first is an Israeli tank which can whip around in a small circle and protect the fort at the same time. The second is an old fashioned bread truck with a Franklin engine. The driver can propel that baby down the street either standing up or pulling out the spring seat from the side. Like all other of Staley’s masterpieces, it is in impeccable condition.

As Staley collected cars, he concentrated on his favorites, the Franklins. But, he didn’t turn away when another car caught his eye. And these cars went into the garages where they waited for the Staley treatment. The treatment takes place in the main garage where the automobiles are beautifully restored to working order. Every detail is attended to as if under a microscope. The “master” is not alone in his work. Staley employs a mechanic, a woodworker and a painter. The paint room is off to the side with jets for the applications and hot lights for drying. “Car collecting is an incurable disease,” said Staley. “Once you got it, you got it.” and once he started, it was impossible to stop. And what does his wife think of all this? Staley said she would throw up her hands and say it was silly but she was really pleased. “Secretly, I think she enjoys it too.”

Staley said when Dick L’Hommedieu approached him about mounting a collection in Norwich, he was already mulling over offers from other places. But, he said, there was no follow-up on these proposals. Chenango County was prepared to put action behind their ideas and so Staley became vital to a tourism package being crafted by county officials. Staley said then Chairman of the Board Cliff Crouch was particularly strong in his support. He liked who he saw and he saw so he made a commitment. He said the county support will be heightened by others, including the Franklin Club. “The big idea is to get people to the area,” said Staley. And the man behind the dream will be doing more than visiting his autos in the near future. He intends to be available to show the cars to visitors. It is one of the things he likes best. And he adds a cautionary note. “They should start soliciting others to donate cars to the museum,” he said. Staley has a vision for the Northeast Classic Car Museum. He would like to see it expand. There are others cars that should be shown. And, added the farmer from Lincklaen, “They should get farmers and some of their equipment in there.”

George Staley had a dream. As a little boy, he loved cars. As a man, he made them his own. He has not stopped dreaming his dreams. There are a lot of cars in this old world..